Nothing had prepared me for the deep shock of having to lie about your own name. From my mother’s breast I had imbibed the certainty that Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, and Jacob, Leah and Rachel were my parents and grandparents, no less than my own father and mother. The Torah of Moses and its dozens and dozens of commentaries and super commentaries, much of which I could recite without a book, had opened me to a glorious world that had made the Jew the most exalted being on this earth.

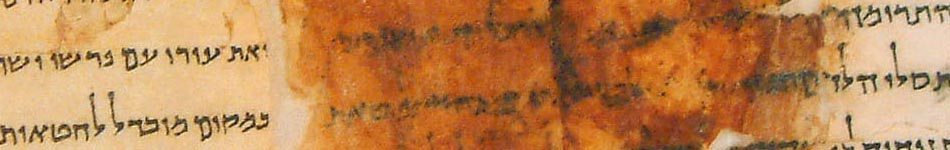

Each word of the Torah could be interpreted seventy times, nay, perhaps seventy times seventy. There is not enough paper in this world to write all the meanings of the first of the Torah. Take the word “Bereshit.” Ibn Ezra, Ramban, Ralbag, Seforno, not to speak of the Rambam, each gives a different meaning for Bereshit. There are even some like Spinoza who believe there was no beginning, no such thing as Bereshit.

But surely Spinoza betrayed his master Maimonides, surely he deserted his people by denying Bereshit. Did not the ten hours that passed from four o’clock in the morning to two in the afternoon testify to the truth of Bereshit? What was occurring this moment in Ozerow except Tohu Va-Vohu? By changing a single letter in the word Bereshit (the “sh” into a “ch”), we can find the word “Aharit,” (end) in “Bereshit” (beginning).

What a fool you are, Ben Zion, I said to myself. You are changing from a pure rationalist into a sheer mystic.

Yes, but your name is now not Ben Zion Wacholder, as given to you at your birth, but some stolen appellation, Waclaw Kaczinski, a forged baptismal certificate of a non-existing Christian. Who am I, Ben Zion or Waclaw? Is this the beginning or the end?

For the time being ,I was both Bereshit and Aharit. Starting from nothing and returning to nothing. If I could turn into a goy in ten hours, surely there must be some truth in metempsychosis. Now, however, the Zelem Elohim was returning into my neshome. I was Ben Zion again, visiting his cousin in Zawichost, a fellow descendant of Abraham.

It was after two o’clock in the afternoon when I entered cousin Eli’s house. The wealth of this place—the carved furnishings, thick rugs, highly polished chairs, mahogany desks—contrasted sharply with broken furnishings I had just left behind for the Polish occupiers. Before the war this front room served as a bank and three years of German occupation hardly touched the household’s apparent prosperity.

Unlike Ozerow, which was located on a main route, the road to Zawichost required a detour to a town which lay on the Vistula but had no bridge to cross the river. The Germans hardly ever ventured there so the town was left alone, much like Ozerow. Ozerow had become populated with people from Vienna, Warsaw, Lodz, and Wloclawek who related some of the brutalities being perpetrated against the Jews. Zawichost being a ferworfene place was immune from this influx. Zawichost was markedly less wounded than the surrounding towns. It would have been unimaginable in Ozerow to display a typewriter to whoever entered the front room. The German’s recent excursions into the town for rape and destruction would have long taken care of such luxuries. But here they were standing on immaculately polished desks.

The deep layers of animal and human excrement that covered my body from top to bottom and the emaciated face behind the dirt made a poor impression on cousin Eli and his wife. Cousin Eli’s first words were: What are you doing here? Why didn’t you use the back entrance or the basement? His wife added that she had never seen anyone dirtier than me. I did not say a word, but indicated with a motion of my head that if they if I was not welcome I was ready to leave. Of course, I had nowhere to go. I was penniless, thoroughly exhausted, famished and absolutely shocked from the preceding events. Still, it was not in my nature to beg. I’m an akshan who stubbornly eschews submission or humiliation. I would sooner steal than be humiliated by begging.

I turned around and began walking to the exit without saying goodbye.

In a way this scene expressed the family feud that had grown between my father and Eli’s father. My father never failed to mention Uncle Zalmen’s squandering, not to say misappropriation of aunt Simtche’s naddan and the inheritance due to him. Uncle Zalmen in turn must have felt that Father and Simtche were not sufficiently grateful for the care that he had bestowed upon them.

I barely opened the door to the outside when Eli and Gittele called out for me not to go. I washed up a bit and was offered freshly baked rolls, butter, herring, sardines, Swiss cheese, cookies, milk and ersatz coffee, a sumptuous meal and as much as I wanted. Food never meant much to me but after a day of nearly fasting, my stomach demanded nourishment. While I was eating, Eli and Gittele never ceased asking me what took place in Ozerow, but I would not respond. After the meal, I briefly outlined what had happened yesterday and what I thought was happening this moment in Ozerow and what will no doubt take place in a few days here in Zawichost.

As if my words were bullets Eli and Gittele began to shout incoherently, crying in a voice that reminded me of the women who would come into the Beth Hamidrash, where we were deeply engrossed in the Talmudic tomes, open the ark wherein the sacred scrolls of Scripture were standing, and hysterically ask God’s forgiveness for their unforgivable sin, as long as their beloved husband or child be spared death. I tried to calm my cousins, in vain.

Gittel, or Genia as she preferred to be called, grew up in Warsaw during the World War and had become deeply imbued with Germanophilia, evident in the freshly oiled editions of glossy leather bound editions of Goethe on her shelves. Years ago, when passing by Zawichost, returning from the Yeshivah, how much would I have given to read the Gothic letterings in the neatly arranged volumes of German Classics.